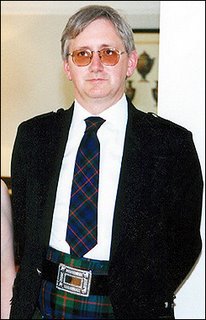

Finally I found Craig Murray and he kindly gave me a very lengthy but amazing interview. The following is just the first part of it:

Finally I found Craig Murray and he kindly gave me a very lengthy but amazing interview. The following is just the first part of it:D: As far as I know, the book was supposed to be in bookstores on 1 June, but it was released a bit later. Do you know why?

CM: Yes. Unfortunately, the British Government kept issuing legal threats against the publisher and demanding the book not be published. That resulted in a very lengthy and expensive process of legal consultations before it could actually be released.

D: I see. And could they explain why it shouldn’t be published?

CM: The British Government claims the right to approve memoirs by former government employees and says, without that government approval they are not allowed to publish them. And in my case they refused to give approval. In fact, we believe they don’t actually have any legal authority to back the government’s claim. Because this is a country where at least until recently we were supposed to have freedom of speech. So. We’ve gone ahead and we are waiting to see if the government attempts to take legal actions against the…

D: Actually in many parts of your book you note that the British Government has censored a fact. Why and how were they censored, and by whom?

CM: During the process of attempting to get clearance from the British Government to publish the book, the government asked me to make certain changes to the book. I made those changes on the understanding that if I made the changes they would give me a clearance to publish. However, even after I made the changes, they still wouldn’t give a clearance to publish. I have, therefore, taken the step of putting the information that was censored onto the web. Initially, on my web site, but now on many other web sites. There are links given in the book by which you can get the information that was censored out of the book.

D: Now, let’s talk about your mission in Uzbekistan. Before putting your step on the Uzbek soil, did you really know where you were going to and what sort of challenges you’d face?

CM: I didn’t really know a great deal. I only had six months between leaving my job in Ghana and arriving in Uzbekistan. In that time I had to learn Russian. I started then not knowing any Russian at all. You’ll understand to get the not speaking Russian at all to be able to work in the language in six months was quite a task. So, I was concentrating enormously on language training. I had also a week of briefing on Uzbekistan in which I was told essentially that it hadn’t changed much since Soviet times. And I was told about Uzbekistan’s potentials in oil and gas reserves and about possible routes for gas pipelines in Central Asia. And also, of course, about Uzbekistan’s position as a United States’ ally and part of the coalition in the so called War on Terror… but it didn’t actually prepare me at all for the real conditions in the country.

D: Afterwards you faced lots of human rights issues in Uzbekistan, but hadn’t you encountered similar problems in your previous designations in Nigeria, Poland or Ghana?

CM: Ghana is a very free country. It’s a democracy with a good human rights record. Nigeria had a certain amount of problems, but it wasn’t nearly as bad as Uzbekistan. But, you know, Uzbekistan is possibly… Well, in fact, Uzbekistan is certainly one of the five worst regimes in the world. One of the five most totalitarian regimes in the world. So, the chances of encountering anything like it anywhere else are quite unlikely.

D: In a private talk with a former British Ambassador whose name is mentioned actually in your book, he had criticized your way of approach towards human rights issues in Uzbekistan. Indicating difficult diplomacy during the Cold War he had said: “For instance, in Stalin’s Soviet Union British Ambassadors knew that millions of people were vanishing under his oppression, but they didn’t want to risk British-Soviet relationship by raising their concerns and questions publicly. But you didn’t do that in Uzbekistan. Do you think it was a mistake?

CM: I think it was a big mistake not to raise human rights concerns in the Stalin’s Soviet Union. Those were different times. Foreign Office doesn’t move with the time. A lot of old British Ambassadors are very old-fashioned crusty people. The truth is that maybe in 1930s people didn’t care too much about human rights. This is the year 2006, and fortunately, we do care now about human rights.

D: The book is called “Murder in Samarkand” referring to the tragic death of a grandson of Professor Jalal Mirsaidov, who’s a Tajik dissident in Samarkand. His grandson’s dead body was found on the day after you met a group of Tajik dissidents in Samarkand. Did you finally find it out if the 18-year-old guy lost his life because of your visit or was the official version of the incident true? They had said he died of an overdose.

CM: Well, the official version of event definitely wasn’t true, because the guy’s arms and legs had been broken, one hand had been badly burnt and he’d been killed by a blow to the back of the head which smashed his skull. So, plainly the official version that he died of an overdose was a simple lie. I believe in my investigations that he was killed. Although the body was found early the next morning, he was actually killed the same evening that I was meeting with the dissidents. I believe that he was killed because of that. I was told by the Russian Ambassador that he had obtained information from his contacts with the Uzbek security services that that was the case and he had been killed as a warning to dissidents not to meet with foreign embassies. And this was the time when the Uzbek government and the-then-Hakim (Ruslan) Mirzayev were cracking down especially hard on the Tajik community of Samarkand in an attempt to enforce further a kind of Uzbekization of Samarkand.

D: While reading your book I felt that you sound quite sympathetic to ethnic Tajiks in Uzbekistan. Why is that?

CM: Well, I think, everyone in Uzbekistan suffers terribly from the regime. But ethnic Tajiks have particular problems, because they are suffering from an abuse of their minority rights, they are increasingly suffering from linguistic discrimination, closure of Tajik-speaking schools. And so a kind of Uzbek nationalist policy is being pursued by the government.

D: Had you given any particular advice to Tajik dissidents to fight for their rights in a more effective way? Since, as you claim in your book, pressure upon them is increasing and for example, from 80 Tajik schools in Samarkand just 12 have left.

CM: Yes, I think, they have to do everything they can to keep their culture alive. Plainly, at the moment it’s so hard for them to organize any open resistance, because we’ve seen at Andijan and elsewhere, what this Uzbek regime will do to anybody who openly tries to organize any resistance. For the moment, they have to try to keep their culture alive by continuing to speak their language at home, teaching their children, holding cultural events and those things. And then, waiting for better time… One of the things I found very sad is the fact that other communities from the same linguistic group don’t pay any attention. I think Iran should have a responsibility to pay some attention to the plight of Tajik-speaking people. But Iran pays no attention whatsoever. Tajikistan, of course, is a very small, a very weak state and not able to do much, but it would be helpful if Tajikistan would openly express concern at what's happening to the Tajik minority in Uzbekistan.

D: But did you give any particular advice to Tajik dissidents when you met them?

CM: No, I was there really for the purpose of documenting their difficulties and things with their individual cases, in which we could make representations or… But I didn’t expect that individual case to turn out to be the murder of my host’s grandson, of course.

D: As it’s mentioned in your book, Nadira speaks Persian too and she’s from Samarkand’s suburbs. Is she an ethnic Tajik as well?

D: As it’s mentioned in your book, Nadira speaks Persian too and she’s from Samarkand’s suburbs. Is she an ethnic Tajik as well?CM: She’s part-Tajik part-Uzbek.

D: In your book you recall your only direct encounter with Gulnara, Karimov’s daughter. Seemingly, you were pleasantly impressed by her down-to-earth behavior and you notice: “There didn’t seem to be obvious darkness behind her laughing eyes” and you ask yourself: “Was she really behind the corrupt acquisition of all those businesses, the closing down of rival companies, the massive bribes from huge energy deals?” So, did you find an answer to that question finally?

CM: Yes, I think, there is overwhelming evidence that she’s very actively engaged in the acquisition of a huge amount of wealth in the Uzbek state through privatization, monopolies and acquisition of companies. And she’s involved in much shadier activities as well, including involvement in sending young women to the Gulf who end up as prostitutes. So, I think, it’s a paradox. When you meet Karimov, he seems like a dangerous, potentially violent, very strong man. You have no difficulty in believing he has done everything he’s done. Because he comes across as a powerful, potentially vicious person. His daughter doesn’t come across that way at all. She comes across as extremely nice when you meet her.

(to be continued)

1 comment:

that's splendid that you got him into your Program! and I GOT THE BOOK!!! Who will not beleive that Satan's accomplices live among us after reading the book.

Post a Comment